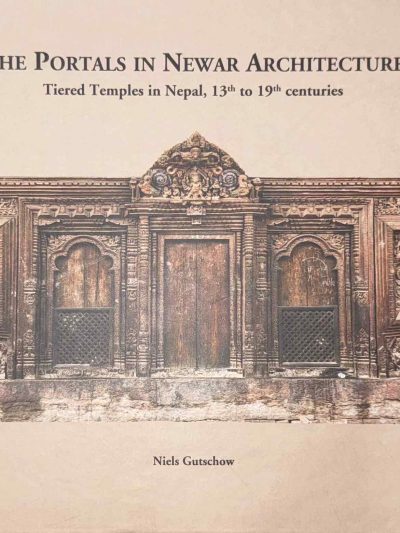

Description

The Origin and Development of the two-tiered temple

Preliminary remarks

In a “backward glance”, written in the 1970s, Mary Slusser convincing y demonstrates “that Nepali architecture is a living remnant of the Gupta tradition (3* – 7th centuries)”%. She further elaborates, however, that “we cannot know whether temples like those of Gupta India ever actually stood in the Kathmandu Valley”. And she comes to the conclusion that the many Gupta-style fragments scattered at historic sites provide only limited evidence of stone architecture in the Licchavi period (5ch to 8ch centuries).

Similarly, Ulrich Wiener traces the roots of the architecture in the Kathmandu Valley from architectural details that survived from the Kushan and Gupta periods (2nd – Gth centuries) and that present striking similarities to the iconographical and structural elements of North India and Nepal’. We know nothing about the timber architecture of the Licchavi period, as the carliest, recently radiocarbon-tested fragments of windows and struts of Buddhist monasteries date to no earlier than the 9th_11th centuries.

From the 5th to the 16th century

Since only the single-tiered caitya temple near Itumbaha and a sikhara temple within the compound of the Pasupatinatha temple predate the Indresvara temple in Panauti, it is open to speculation what the early, monumental 5ch or G*-century temples at Deopatan and Cangu looked like. The inscribed victory pillar of the 5th century at Cangu, which once supported a monumental Garuda, indicates the early existence of a grand temple. Since the previous temples were destroyed and lost in earthquake and fire, the present structure originates from 1712, most likely on a reduced plan.

The earliest available documentary evidence referring to Lord Pasupati dates to 6011º but does not make mention of a temple. According to the Gopalarajavamsavali, a chronicle from the end of the 14th century, the donation of gilt copper roofs to Pasupatinatha in the early 12th and late 13th centuries suggests the existence of a large built structure for a deity who, from the 7th century on, was the tutelary deity of the kings of the valley. Since the earliest times they referred to themselves as ones “favoured by the feet of the Lord, the divine Pasupati” (bhagavat-Pasupati-padanu-grahito). In 1381 the supreme deity was even addressed as the “sovereign lord of Nepal” (nepaladhipati) “.

For both temples, at Cangu and at Deopatan, wide-ranging destruction is reported as being inflicted in 1349 by Sultan Shams ud-din Ilyas’s troops. The Pasupatinatha temple was rebuilt either in 1360 or 1381, or even as late as 1413, while for the Cangu Narayana temple the rebuilding was not recorded. However, repairs were undertaken in 1506, as the structure had suffered damage from an earthquake.

Since no trace of earlier structures exists, the shape of the present temples, renewed after total loss and dismantling in 1697 and 1708, must be seen as copies of the preceding ones. The act of copying pertains to the two-tiered shape and the structural scheme of the tripartite portals, while the iconographical and decorative details underwent considerable change.