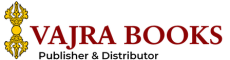

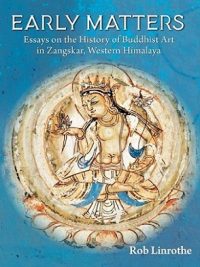

Description

This book is focused on the art in the remote valleys of Zangskar, a region of the union territory of Ladakh in northern India. It proposes that, first, the people and institutions in Zangskar produced a treasury of understudied Buddhist art in the form of architecture, sculpture, and painting and that, second, examination of this corpus models the formation of early visual culture in the western Himalaya as a whole. Its chapters provide correctives to the reduction of this region to a miniature or provincial Tibet, particularly in the early periods of extant sculpture (between the seventh and eleventh centuries) and of painting (tenth to thirteenth centuries). It locates Zangskar as its own center intersecting and in contact with a range of Buddhist visual production sites surrounding it in all directions, including greater Kashmir, Khotan, Central Asia, northern and eastern India, Tibet and western Nepal. The analysis of early Zangskari Buddhist images is a much more complex-and interesting-story of cultural development and inspiration than the simplified Indo-Tibetan narrative which ignores the agency of Zangskar’s artists, merely attributing forms and objects to invisible Tibetan hands.;The first chapter of Part I, Theoretical and Methodological Matters, takes a historiographic approach to highlight misunderstandings in regional nomenclature. The second chapter reconsiders the relevance of the influential Tibetologist and art collector, Giuseppe Tucci, in the practice of art history on Tibet and the western Himalaya. The three chapters of Part II, Early Matters, successively examine the earliest low relief stupa engravings on stone in Zangskar and Ladakh, the early figural carvings and paintings in the area, and the important early Esoteric Buddhist sculptural and painted program at the Malakartse Khar site in Zangskar. The latter are compared to other extant sites in western Tibet. The sixth chapter, the first of three in ;Part Three, examines two radically different sets of Mahasiddha stone carvings in two neighboring villages of Zangskar. Chapter 7 recounts the discovery, recovery, expansion, and renovation in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries of twelfth- to fifteenth-century structures, paintings, sculptures, and other finds at Karsha village by the Karsha Lonpo Sonam Wangchuk and his family. The final chapter considers a single painting of Sarasvati of late fifteenth- or early sixteenth-century date preserved in the Phugtal Monastery of Zangskar, conjuring the embedded religious and social significance to its monastic sponsor who is depicted at the bottom of the painting. The 585 illustrations, with many details, represents an expensive documentation of culture heritage currently threatened by climate change and the lack of protection for objects traditionally displayed in open view.